SHERRY NOTES AND STYLES

The sherries purchased for my tasting all came from Majestic wine shops and are as follows:

MANZANILLA PASTRANA very dry sherry. very fresh and well balanced with hints of green fruits and slightly salty finish

GONZALES BYASS AB AMONTILADO dry tawny colour, hints of ripe raisins and herbal notes. delicious

GONZALES BYASS ALFONSO OLOROSO deeper tawny colour with hints of oak ageing, nuttiness and dry. again full bodied and delightful

APOSTOLES PALO CORTADO 30 YR OLD a rare taste of something special. This 30 yr old is truly worth a visit.

GONZALES BYASS LEONOR PALO CORTADO Another taste of something special. Hints of oak, caramels, and nuttiness. long and pleasant aftertaste

PEDRO XIMENEX VIEJO HIDALGO one of my go to dessert drinks. Almost black in colour, delightfully sweet and one glass is never enough.

Sherry is perhaps the most undervalued, unappreciated alcoholic drink in existence. It has often been drunk only at Christmas time or as an aperitif at parties. But times are changing and more and more younger people are enjoying sherry cocktails, or as a long drink mixed with tonic over ice or, as I like it, on its own. ( I like the long drinks as well)

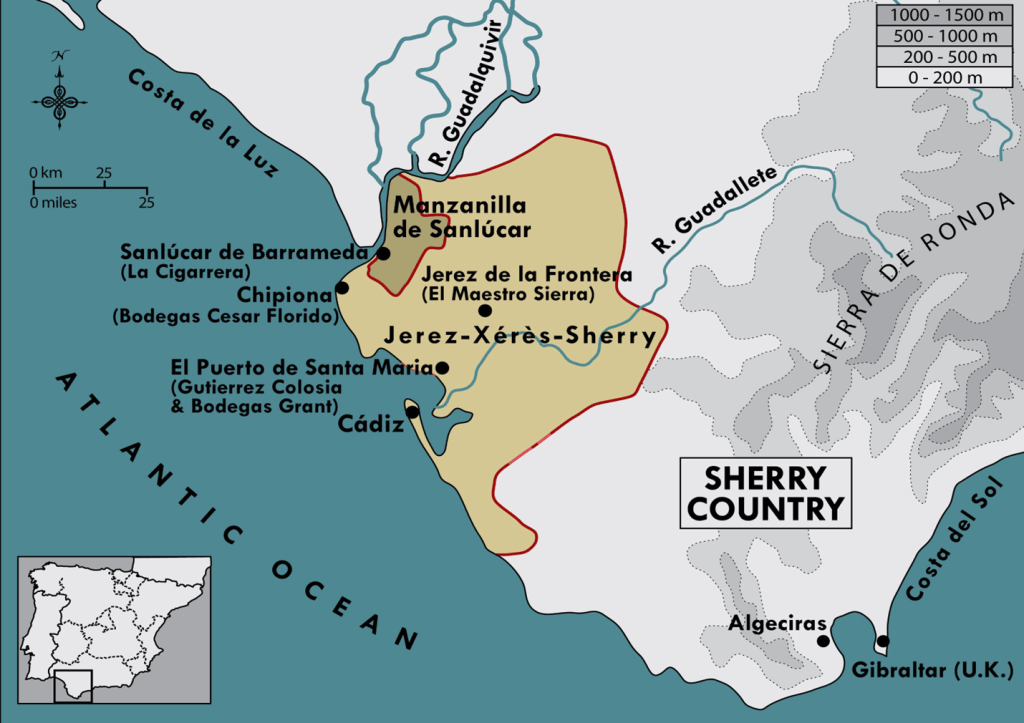

It is made with the Palomino Fino grape, which is grown in chalky albariza (‘snow white’) soils in Jerez, located near the southern tip of Spain. The basic wine, which is low in acidity, is rather dull at this point – it is the next stage that gives Sherry its magic.

ALBARIZA SOIL

Albariza soil is a unique, chalky soil found in the Jerez region of Spain, renowned for its exceptional water retention and suitability for growing Palomino grapes used in sherry production.

Composition and Characteristics

Albariza soil (whose name comes from the Latin word “alba,” meaning white) is primarily composed of calcium carbonate, clay, and marine fossils or diatom sediments date back millions of years ago. Andalucía, the southernmost region of Spain, to which the Jerez region belongs, was submerged under the sea around 60 million years ago (Oligocene era). Over time, rock formations and areas of submerged ground gave way to the complete retreat of the sea, creating isolated and shallow lakes. During this process and because of the sea’s dissipation in the area, the soil (known as “barros”) found in these in marshlands close to the Guadalquivir or Guadalete rivers at the lower part of the hills is rich in organic matter. On the other hand, in the higher zones, the fossils of marine organisms (such as diatoms) and algae accumulated on the ancient seabed came out to the “surface” of the land giving birth to our “albariza”, the iconic soil.

This type of soil is not exclusive to coastal areas or to Jerez. There are other regions within and outside the Iberian Peninsula where remains of marine fossils and diatoms have been found although they are now far from sea or water masses. Champagne is one such example. Just as in Andalucía, this region was uplifted due to the collision of the African and European tectonic plates. This historic and geological phenomenon caused the emergence of mountain ranges like the Alps. This is why it’s possible to observe diatoms and fossil remains at extreme altitudes, such as 1,500 meters above sea level, or distances of over 200 km from the sea.

The main characteristic of this soil, and the primary reason why it’s highly valued among growers and wineries, is its water retention ability. This soil can hold moisture collected through water during the rainy season (November – April) and store it in its deepest stratums, providing nourishment to the vine throughout its life cycle. This compensates for the low levels of organic matter the soil has and also supplies necessary nutrients to the vine.

Due to its highly porous structure, water storage occurs in the form of moisture. Albariza soil cannot fully absorb water. This is advantageous for the vine, as there’s no risk of waterlogging or drowning. The soil is porous also allows for a continuous and steady airflow, allowing the plants to “breathe.”

Furthermore, its colour causes light reflection. The sunlight waves are repelled, avoiding overheating, and preventing them from being projected towards the vine. Thus, both soil and vine do not struggle during the hottest summer months reflecting light and keeping the roots and plant cool, even in extreme situations like drought or heatwaves.

FINO Sherries head down one of two paths: Finos, which are light and delicate, and Olorosos, which are darker and richer. After grape spirit is added, which fortifies the wine to not more than 15.5% for Fino and 17%-18% for Oloroso, depending on the style, a layer of flor (yeast) develops across the surface of a Fino, which protects it from oxidation, and ensures that it retains its subtle, pale appearance. Finos are bone-dry, but very refreshing, and should be served chilled.

WHAT IS FLOR

Flor is a special type of local yeast from the Andalusia region in Spain. It is useful for making Sherry (Jerez) as it forms a cap on top the wine in their barrels and protects the wine from oxidation. It also creates an environment for micro-oxidation that gives the styles of Jerez their unique character.

Manzanillas are similar to Finos, but come from the coastal town of Sanlúcar de Barrameda, which has a more humid climate, so the layer of flor is thicker, and grows permanently. As such, the Sherry has a more appley character. Aged versions are known as Manzanilla Pasadas, and are nuttier with more concentration.

The layer of flor which forms on the surface of Sherry wines is referred to as the “veil.” It can grow as thick as 3/4 of an inch thick. This special yeast is only indigenous to the specific climate in Southern Spain. Immediately following the fermentation of the base wines for Jerez, flor will begin to form.

Flor is this yeast that divides all the wines made in the Jerez de la Frontera region into two separate categories:

Biologically-aged Sherry – including Manzanilla and Fino styles

Oxidative Sherry – including Amontillado, Oloroso or Pedro Ximénez

NOW A LOOK AT THE STYLES

OLOROSO True Olorosos are rich and full bodied and either dry or sweetened by blending sweet wines, some made with sun-dried Pedro Ximénez grapes. A good Oloroso will have an alluring aroma (Oloroso means ‘aromatic’ in Spanish) of nuts, caramel and coffee, but no cloying sweetness.

AMONTILLADO A style of Sherry which begins life as a Fino, but the winemaker allows the flor to die, thus exposing the wine to the air. Amontillados are amber in colour and have a nutty, dry to medium-dry character. They have more body than Finos, and are excellent with more robust dishes.

PALO CORTADO It’s the maverick of the sherry world, a fascinating accident that happens in the cellar. Think of it as a wine with two souls. This seeming contradiction is what makes it so sought-after by wine lovers. The rarest style of Sherry, combining the fragrance of an Amontillado with the body of an Oloroso. Palo Cortado is a rare variety of sherry that is initially aged under flor to become a fino or amontillado, but inexplicably loses its veil of flor and begins aging oxidatively as an oloroso. The result is a wine with some of the richness of oloroso and some of the crispness of amontillado. Only about 1–2% of the grapes pressed for sherry naturally develop into palo cortado.

To truly appreciate Palo Cortado, you have to understand its unique place in the sherry family. It isn’t made through a direct, repeatable recipe like other sherries; it’s more of a wine that “happens” when specific, uncontrolled conditions align in the cask. This unpredictability is central to its allure.

What does the name “Palo Cortado” actually mean?

The name itself tells a story of its discovery. In the sherry bodegas of Jerez, cellar masters use chalk marks on the barrels to classify the developing wines. A vertical slash, or “palo,” would mark a cask of young wine (a “fino”) showing exceptional finesse, destined for biological aging under flor.

If, for some unknown reason, that wine’s flor layer died off or weakened, the cellar master would have to intervene. They would fortify the wine with more grape spirit and re-route its destiny toward oxidative aging. To signify this change, they would draw a horizontal line through the original slash, creating a “cut stick” or “palo cortado.” This symbol was a note to all: this wine had changed its path and was now something else entirely—something special.

Why is Palo Cortado considered so rare?

Its rarity stems from its spontaneous, almost accidental, creation. You can’t just decide to make a Palo Cortado from scratch. Winemakers select the finest, most delicate base wines to become Finos. Only a tiny fraction of these casks—less than 1%—will naturally and inexplicably lose their flor.

Historically, the exact reasons were a mystery, often attributed to subtle variations in the cask’s wood, temperature, or humidity. While modern winemaking has more control, true, traditionally-emerged Palo Cortado remains an exception, not the rule. This scarcity, combined with its complex character, makes it one of the most prized and often more expensive categories of sherry.

What is the role of “flor” and why does it disappear?

Flor is a film of native yeast that forms on the surface of the wine inside the barrel. It’s the magic ingredient for Fino and Manzanilla sherries. This yeast layer consumes remaining sugars and glycerol from the wine, making it bone-dry and light-bodied, while also shielding it from oxygen. This is called “biological aging.”

In the case of Palo Cortado, this flor layer dies off unexpectedly. This can happen for many reasons—a slight temperature fluctuation, a minuscule variation in the wine’s composition, or a change in the barrel’s humidity. When the flor vanishes, the wine is left exposed to air, and “oxidative aging” begins, just like an Oloroso. The winemaker recognizes this change, fortifies the wine further to around 17-18% to protect it from spoiling, and re-classifies it as Palo Cortado.

PX One of the richest and sweetest wines in the world, Pedro Ximénez is made from grapes of the same name that are dried in the sun after picking to concentrate the flavour. PX, as it is also known, has a thick, almost treacly texture, and an intense, rich flavour.

30 yr old

Made from partially sun-and-air-dried grapes, which are then pressed, fermented, fortified, then aged in Gonzales-Byass’s Nectar solera. A proportion is transferred to the Noe solera, where a blend of vintages of at least 30 years-of-age create this unique sherry. Thick, sticky, luscious and viscous, this sherry is super-sweet yet hugely complex and involving. Flavours of dates, cinnamon, clove, treacle and caramel combine like a silky, liquid pudding. Drink with Christmas pudding, or drizzle over quality vanilla ice cream for an indulgent treat. In 2023, this wine won an IWSC gold award.

Blending / ageing of sherries

A unique feature of Sherry production is the solera system. Sherries are not vintage-dated in the way that most wines are; instead, the oldest casks are frequently topped up with Sherries from younger casks to maintain a consistent style. Solera takes its name from suelo, meaning ‘soil’ or ‘floor’ in Spanish; in the bodega, the oldest casks will be those nearest the ground. Each year, a proportion of the oldest wines will be removed from barrel, and replaced with wine from the next-youngest batch, and so on. This ensures consistency, and the addition of younger wine helps to sustain the flor in Finos. And the fact that no more than one-third of the wine may be withdrawn in any one year means that the youngest Finos and Manzanillas will be at least three years old before they are released.

Food-matching ideas

- Fino: salted almonds, olives, anchovies, cured ham, paëlla

- Manzanilla: seafood

- Manzanilla Pasada: richer dishes like crab

- Amontillado: tuna stewed in onions, hard cheeses

- Oloroso (dry): mature Cheddar, Parmesan

- Oloroso (sweet): blue cheese, Christmas cake

- Pedro Ximénez: chocolate desserts, Christmas pudding, vanilla ice cream

Leave a comment